Author : Russell Horng

For IP Forum under Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) 19 July 2001

Contents

I. Overall View & Recent Signs

II. Interpretation of Claim(s)

III. Auxiliary Rules for Implementing Patent Infringement Assessment

I. Overall View & Recent Signs

A. Overall View of IP Protection in Chinese Taipei

Chinese Taipei is not a signatory to the Paris Convention, the Berne Convention, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) or other international treaties/conventions concerning intellectual property rights (“IPR”) protection. However, the rapid transformation of Chinese Taipei from a developing society into an economically strong society is quite remarkable and reflects Chinese Taipei’s desire to take its place among the developed members of the world. To sustain its reputation as one of the most economically powerful members in Asia, Chinese Taipei continues to revise its laws and regulations, in particular, those concerning the protection of IPR, to keep pace with its development.

In the traditional Chinese society, appropriating other people’s ideas for personal advantage is considered “borrowing the wisdom of others” and therefore is not deemed either morally wrong or illegal. For this reason, over the past years, local industries have not fully appreciated or respected others’ IPR, and the local courts have not treated IPR infringement as a serious crime. However, this has significantly changed during recent years primarily for two reasons. First, local industries and people have realized the importance and true value of IPR through educational programs sponsored by the government. Secondly, the innovative abilities of local industries have been greatly developed and market conditions have become so competitive that industries demand effective, global protection of their own technologies.

B. Chinese Taipei – A Great Market

High-tech industries are blossoming in Chinese Taipei. Statistics highlights the growing importance of computer-related products to Chinese Taipei’s economy in general, and Chinese Taipei’s industry in particular.

Now, Chinese Taipei is the world’s third largest producer of information technology products and other computer hardware. For example, Chinese Taipei’s aggregate output of semiconductors is only next to the United States and Japan. Chinese Taipei’s impressive market share reflects its role as a dynamic player in the worldwide market of electronic products, computer hardware and semiconductors. For this reason alone, Chinese Taipei has a vested interest in IPR protection.

C. Patent and Technology Commercialization Activities in Chinese Taipei

Chinese Taipei has other valid reasons and motives for its vested interest in IPR protection, as the country forges ahead in the field of technological innovation. Research and development (R & D) expenditure continues to increase dramatically. In step with this development, the number of overseas patents filed by local manufacturers has also significantly increased. According to statistics released by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), Chinese Taipei filed 10,380 patent applications in the US in 2000. This statistics means that Chinese Taipei had the third largest number of patent applications filed in the US in 2000. 5,578 patents were obtained in the US in 2000. Furthermore, according to statistics released by the State Intellectual Property Office of China (SIPO), Chinese Taipei filed 10,778 patent applications in China in 2000. This fact underscores the quality and quantity of the technologies developed in Chinese Taipei over the past few years.

II. Interpretation of Claim(s)

A. The Official Guidelines for Evaluating Patent Infringement

According to Paragraph 4, Article 131 of the Patent Law of Chinese Taipei, the Judicial Yuan and the Executive Yuan shall coordinate with each other in appointing Professional Institutions[1] for patent infringement verification. Since the Courts’ viewpoints for interpretation of infringement have not yet matured enough to set up a standard or guideline, the Courts usually rely on the expertise of the Professional Institutions to render their judgments on patent infringement. To harmonize the standards and steps for evaluating patent infringement, the Chinese Taipei’s Intellectual Property Office (IPO) issued the “Patent Infringement Assessment (PIA) Guidelines” in January 1996. The Professional Institutions are basically obliged to follow the IPO’s PIA Guidelines for interpreting the effective scope of patented claims and to determine whether an accused product has infringed the claims.

B. The Basic Steps to Interpret the Patent Claims

1. All Elements Rule

Chinese Taipei adopts the so-called “All Elements Rule” under which each essential element of a claim or its substantial equivalent must be found in the accused device to constitute literal infringement. In the All Elements Rule, “element” is used in the sense of a limitation of a claim. If the accused device has all elements defined in the claim but further includes additional element(s) to perform additional function(s) without changing the structure and functions of those elements of the claim, the incorporation of the additional element(s) will not avoid literal infringement.

One remaining question is that whether a literal infringement can be found if an accused device omits one or some insignificant element(s) recited in the patent claims. Although the PIA Guidelines are silent on this question, some senior examiners of the IPO are of the opinion that omission of non-essential element(s) which is (are) recited in the patent claims will not avoid literal infringement.

2. Doctrine of Equivalents

The Doctrine of Equivalents has been introduced into the PIA Guidelines to serve as an indispensable step following the “All Elements Rule” determination for evaluating patent infringement. The Guidelines propose the following two tests for applying the Doctrine of Equivalents:

(1) The Interchangeability

The equivalent element performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way and produces substantially the same result as the clement expressed in the claim[2].

(2) The Predictability for Replacement

It is clear or obvious to a person skilled in the art at the time of any alleged infringement that the same result as that achieved by means of the element expressed in the claim can be achieved by means of the equivalent element (e.g., German test).

The PIA Guidelines does not indicate the order in which to apply the dual tests for equivalency, though some practitioners propose that the interchangeable test be applied first.

It must be noted that the “Hypothetical Claim” test under the U.S. litigation practice shall not be applied according to the PIA Guidelines

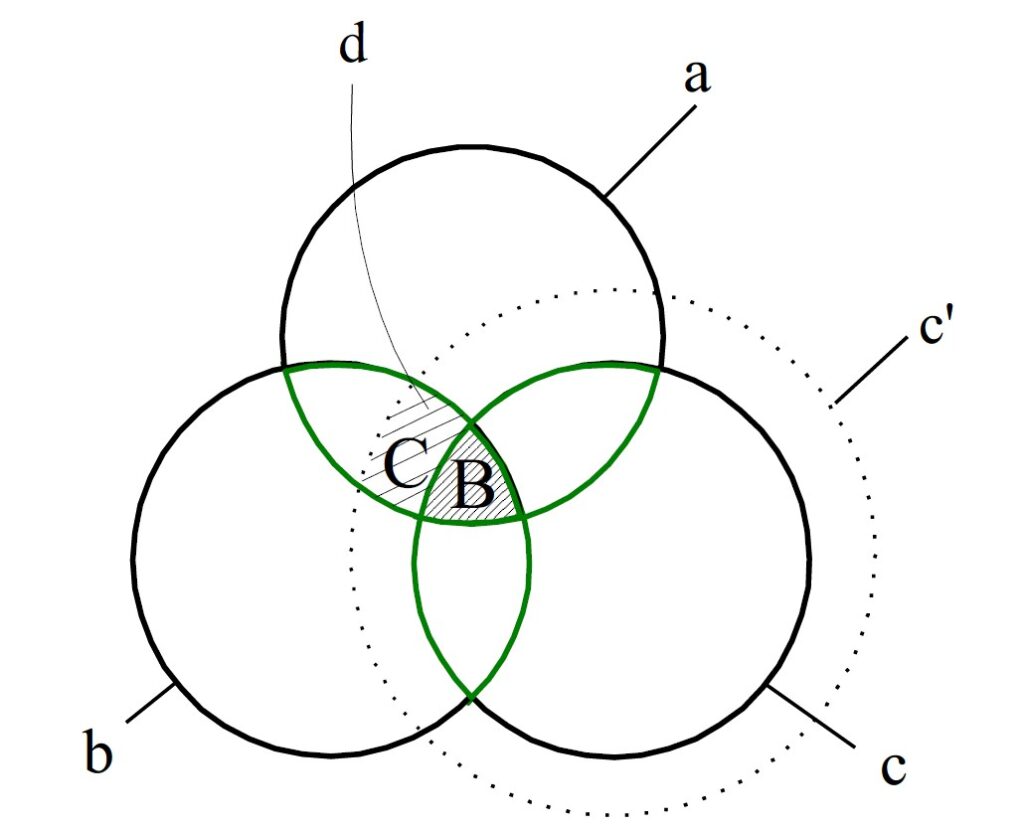

3. Prosecution History Estoppel

The Doctrine of Prosecution History Estoppel has also been introduced into the PIA Guidelines to serve as an indispensable step following the ‘Doctrine of Equivalents’ determination for evaluating patent infringement. In other words, when interpreting the patent claim(s), the patent prosecution history should be taken into consideration as well. The PIA Guidelines proposes a flow chart for conducting patent infringement assessments[3], see Figure 1. Interpretation of the patent claim(s) should not involve argument(s) inconsistent with the statements included in the communications among the patentee, patent examiners and opposition/cancellation petitioners, which form the basis for the patent grant.

Under the Chinese Taipei’s practice, all patent claims shall be considered valid. Furthermore, the general Court is not granted the power to determine the validity of a patent or the validity of any claim thereof. Accordingly, the accused party shall not institute a formal invalidation action with the Court which is in charge of the patent infringement litigation, or argue that the patent or the claim(s) thereof is invalid.

Pursuant to the Patent Law of Chinese Taipei, an invalidation action can only be filed with the IPO. Any party who is dissatisfied with the IPO’s decision must file an administrative appeal with the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA). Consequently, if the party is further dissatisfied with the decisions rendered by the MOEA, he/she must file an administrative suit with the Administrative Court.

Procedure for Patent Infringement Assessment

Figure 1[4]

III. Auxiliary Rules for Implementing Patent Infringement Assessment

A. Other Rules for Implementing All Elements Rules

It is the global practice that the scope of an invention claimed against any infringer shall be determined on the basis of the “claims” of the patent concerned[5]. In addition, patent claims are interpreted from two different angles. That is, “Patentability” evaluated by the IPO during the prosecution procedure (invalidation procedure), and “Enforcement” determined by the Court during the infringement litigation.

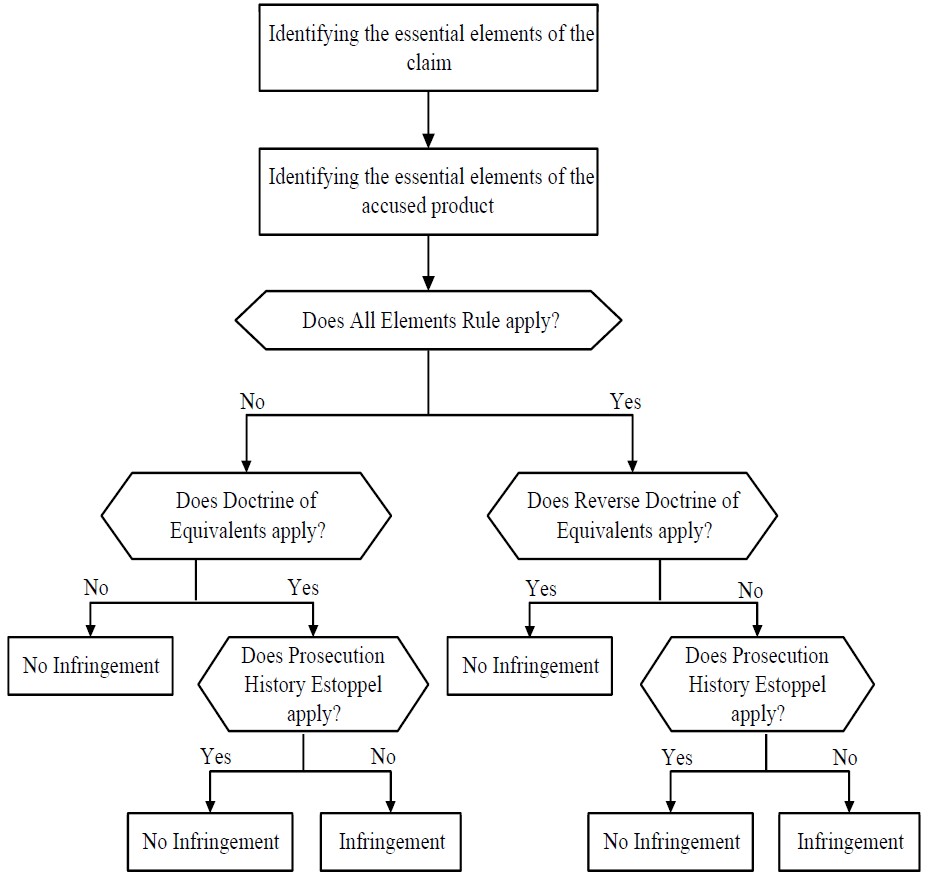

The scope of a claim is defined by the essential elements or limitations of the subject matter sought to be patented. It must be noted that the more the essential elements are, the narrower the scope of patent protection will be. The fundamental logic of the definition of the claims and the relationship between the essential elements as well as the subject matter of the claims can be explained by the following Figures 2 and 3:

Where the first patent claims a stool “A” comprising a seat “a” and at least three legs “b.” The second patent claims a chair “B” comprising a seat “a,” at least three legs “b” and a back “c.” The scope of protection afforded to the stool A by the first patent shall be defined by the seat “a” and the legs “b,” while the scope of protection afforded to the chair B by the second patent shall be defined by the seat “a,” the legs “b” as well as the back “c.”

In general, the following three auxiliary rules can be adopted to facilitate the application of “All Elements Rules”[6]:

Rule of Exactness

The accused product copies the patented invention “exactly.” That is, the accused product includes all essential elements defined in the patented claim without adding any additional element. According to the Rule of Exactness, the accused product will literally infringe the patented claim.

Rule of Addition

The accused product includes all essential elements defined in the patented claim and at least one additional element. According to the Rule of Addition, the accused product will literally infringe the patented claim. Basically, the Rule of Addition shall not apply to material invention patent (i.e. Markush type claims) unless one of the following exceptions exists:

1. If the additional element is a trifling impurity which is so insignificant in quantity and performs no substantial effect to the claimed material; and

2. If the additional element is a neutral compound which is so insignificant in quality and performs no substantial effect to the claimed material.

Rule of Omission

The accused product omits one or more of the essential elements defined in the patented claim. According to the Rule of Omission, the accused product will not literally infringe the patented claim.

B. The Fundamental to Apply the Doctrine of Equivalents

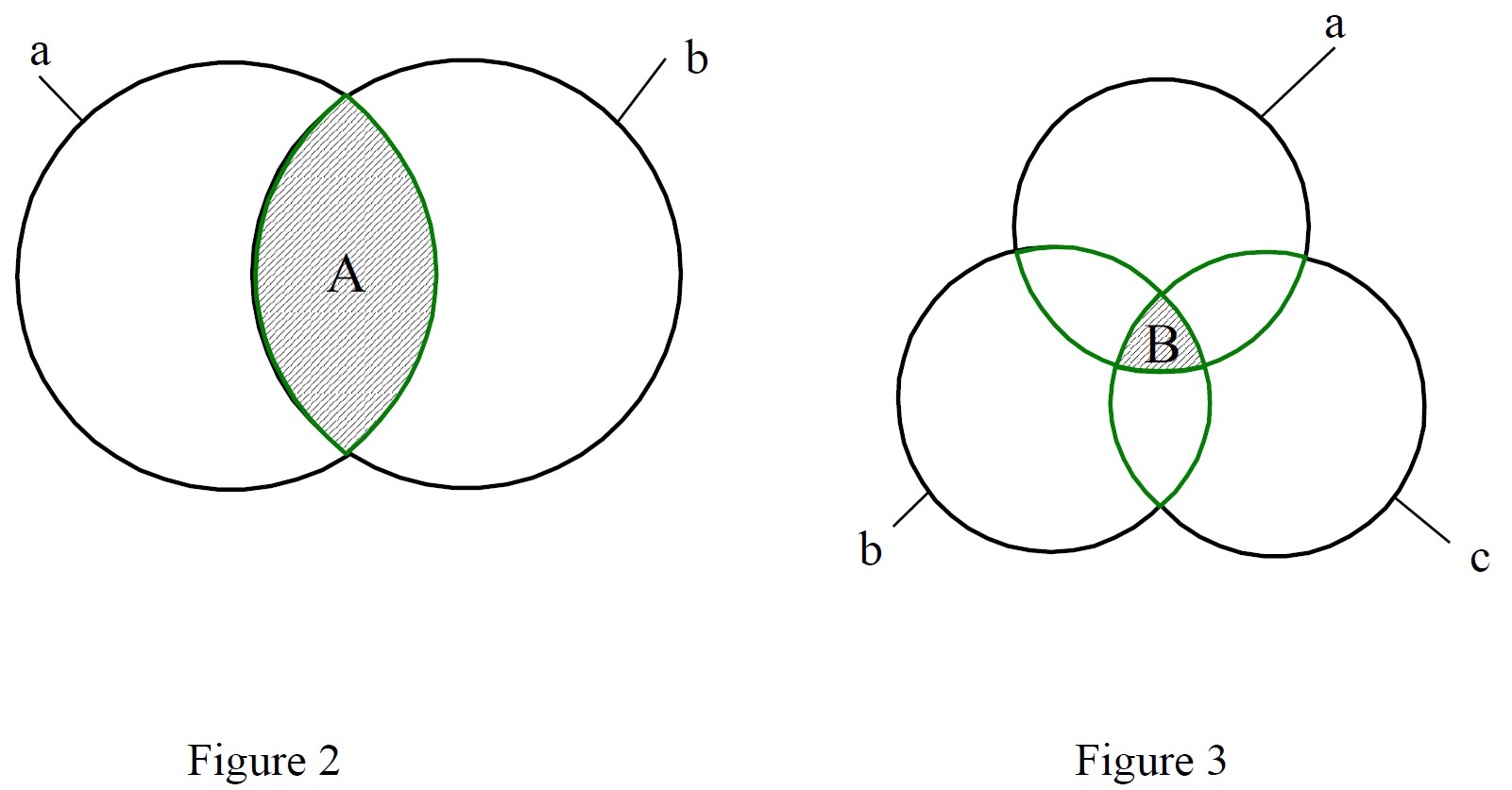

As compared with the “All Elements Rule” determination, the tests of Doctrine of Equivalents are more complicated and comparatively subjective. Normally, a patentee can only enlarge the enforceable scope of his patented claim by giving interpretation, under the Doctrine of Equivalents, to the specific element(s) of the claimed subject matter rather than to the claim itself. We may explain the above condition by a simple drawing, see the following Figure 4:

Figure 4

A patent claims a chair “B” comprising a seat “a,” at least three legs “b” and a back “c.” The accused chair “C” comprises a seat “a,” at least three legs “b” and an element “d,” where “d” is an equivalent of “c.” In Figure 4, the circle “c’ ” defines an equivalent or enforceable range outside the scope defined by the back “c.” The area denoted by “B” is defined by the seat “a,” the legs “b” and the back “c,” while the area denoted by “C” is defined by the seat “a,” the legs “b” as well as the back “c” and the back “c’.” Basically, the enforceable scope afforded by the claim of the patented chair “B” under the Doctrine of Equivalents consists of areas “B” and “C.”

C. Supplementary Definition of the Doctrine of Equivalents

Although the “tripartite test” proposes that the Interchangeability under the Doctrine of Equivalents shall apply if the equivalent element performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way and produces substantially the same result as the clement expressed in the claim, the existing tests for evaluating the Doctrine of Equivalents can hardly satisfy the objective and accurate requirements anticipated by the patentees, the accused parties and the practitioners. Some experts presented the following statements pertaining to the Doctrine of Equivalents:

“Despite attempts at refinement and development over more than a century, the doctrine of equivalents remains imprecise.” ; and

“The Federal Circuit has undertaken to redefine the doctrine in an attempt to create greater certainty in application. The court‘s efforts, however, are both ill-advised and unlikely to succeed.”[7]

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) rendered some judgments which are quite useful for refining the Interchangeability test. The CAFC said in one of the noted judgments: “…evidence of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents requires explanation of why the overall function, way and result of an accused device are substantially the same as those of a claimed device, and why the particular feature in the accused device is the equivalent of the claimed limitation.”[8]

In order to answer “why” the way(s), function(s) and result(s) of the equivalent element of the accused product are substantially the same as those of the specific element of the patented claim, we must exactly identify the way(s), function(s) and result(s) of this specific element defined in the patented claim.

D. The Sequence of Auxiliary Rules for the Doctrine of Equivalents

As indicated above, there are two tests, i.e., the Interchangeability and the Predictability for Replacement, for applying the Doctrine of Equivalents. The PIA Guidelines fail to indicate the order in which to apply the dual tests for equivalency, though some practitioners propose that the interchangeable test should be applied first. For the sake of prudence, it appears to be recommendable that the Interchangeability test be applied first due to its more objective aspect.[9]

E. The Boundary of the Scope Expanded under Doctrine of Equivalents

The tests of “Interchangeability” and the “Predictability for Replacement” are adopted to determine whether the accused product has infringed the patented claim under the Doctrine of Equivalents. However, during the determination of the Doctrine of Equivalents, the following auxiliary rules may be used to evaluate the boundary or limitation of the protective scope afforded by the patented claim according to the Doctrine of Equivalents:

1. The patented claim shall not be extended to cover the prior art because prior art is a part of the public domain;

2. The patented claim shall not be extended to cover an inferior product because the inferior product will not enjoy the advantages of the patented invention and does not involve an inventive step over the prior art. In other words, the claim would be invalid or unpatentable if it is interpreted according to the Doctrine of Equivalents to cover the inferior product; and

3. The patented claim shall not be extended to cover a product that involves breakthrough in technical theory or principle because the invention defined in the patented claim is not developed to such an extent or technical level. In brief, a product involving breakthrough in technical theory may position beyond the teachings and contribution of the patented invention.

F. Possible Impact of the Foreign Patent Infringement Case

On 29 November 2000, the CAFC rendered its well-anticipated en banc decision in Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co. Ltd.[10] This decision may radically and controversially change the law of Prosecution History Estoppel. The majority opinions, authored by Judge Schall, can be summarized as follows:

1. An amendment that narrows the scope of a claim for any reason related to the statutory requirements for a patent will give rise to Prosecution History Estoppel with respect to the “amended claim element”;

2. “Voluntary” claim amendments are treated the same as other claim amendments;

3. When a claim amendment creates Prosecution History Estoppel, no range of equivalents is available for the amended claim element; and

4. “Unexplained” amendments are not entitled to any range of equivalents.

The CAFC addressed in the decision: “When no explanation for a claim amendment is established, what range of equivalents, if any, is available under the Doctrine of Equivalents for the claim elements so amended. Finding its answer in Warner-Jenkinson, the CAFC held that when no explanation for claim amendment is established, no range of equivalents is available for that claim element.

According to the decision, to avoid the application of an estoppel, the patentee must show that the amendment was made for a purpose unrelated to patentability concerns. In other words, the patentee may not rely on extrinsic evidence. Instead, he must argue against the application of Prosecution History Estoppel solely on the official records of this patent’s prosecution.[11] It is believed that the above decision should have influenced the U.S. patent prosecutions and litigations.

Although the CAFC’s en banc decision severly limiting the claims of infringement under the Doctrine of Equivalents has been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court[12], this very pro-defendant decision will certainly carry weight in the near future to Chinese Taipei’s patent practice as well.

[1] The Judicial Yuan and the Executive Yuan have appointed 69 Professional Institutions so far.

[2] This interchangeability test is substantially identical with the U.S.「tripartite test」 or 「Graver Tank Test」, see Graver Tank & Manufacturing Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339 US 605,85 USPQ 328, 1950.

[3] See Page 73 of the IPO’s PIA Guidelines.

[4] Criticisms of the logic of this flow chart and the IPO’s PIA Guidelines can be found in the “”Proposals on the Official PIA Guidelines (I)-(IV),” Russell Horng, NBS (March-November 1997).

[5] Article 56 of the Patent Law of Chinese Taipei.

[6] See Chapter 10 of Patent Law-A Practitioner’s Guide, Ronald B. Hildreth, August 1988.

[7] See Pennwalt Redux-Judicial Uncertainty vs. Procrustean Bed-Maxim H. Waldbaum & David Sipiora (AIPLA Q.J., No. 3, 1991)

[8] Malta v. Schlumerich Carillons Inc., 21 USPQ2d 1161 (Federal Circuit 1991).

[9] See Article 21 of the WIPO draft treaty for harmonizing the patent laws throughout the world.

[10] No. 95-1066 (Fed. Cir. 29 November 2000).

[11] “No Equivalents Claims are Permitted on Elements Amended for Patentability,” Patent, Trademark & Copyright Journal (1 December 2000); “en banc Federal Circuit Redefines The Doctrine of Equivalents and Prosecution History Estoppel,” Finnegan, Hederson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, L.L.P. (5 January 2001).

[12] Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., Ltd., No. 00-1543, review sought 9 April 2001.